If you’ve ever wanted to put aside some money for retirement, you’ve probably noticed that there are an almost overwhelming number of choices when it comes to retirement plan types. There are IRAs, Roth IRAs, SEPs, SIMPLE IRAs, 401ks, 403bs, 457 plans, Qualified Retirement Plans, Profit Sharing plans, and on and on. There are so many choices! And this is just the type of plan (think “vehicle”) to put your money in, you still have to decide the actual investments to pick once the money is inside.

So what I want to do in this post is simply cut through all that noise, and focus on the two most popular account types: an IRA (also called a “traditional” IRA) and a Roth IRA. These two are the most popular for lots of reasons, which I’ll explain in a moment, but think of them like Original Coke and Diet Coke. They are the two original standard options for retirement planning. All of the others can be useful in certain circumstances, but for the vast majority of people, the Roth IRA and Traditional IRA will (or should) play a major role in funding retirement.

One quick caveat: I’m talking about the basic plans outside of your workplace retirement plan, if you have one. I’ll address that option briefly below, but since almost 50% of workers don’t have access to a 401k or equivalent plan, I’ll limit this article to the non-workplace-based options only.

The Basics

The traditional IRA is the original personal retirement plan vehicle, and was created by Congress in 1974. While large corporate and governmental retirement plans (i.e. pension plans) have been around way before the IRA, this was the first time you could have your very own Individual Retirement Account. Essentially, it’s just an account, set aside for you, that you invest for retirement.

The Roth IRA is it’s younger brother, and was created by Congress in 1997. Basically, the Roth IRA is just like the Traditional IRA, except with the opposite tax structure, and a few other minor differences.

The Roth IRA is it’s younger brother, and was created by Congress in 1997. Basically, the Roth IRA is just like the Traditional IRA, except with the opposite tax structure, and a few other minor differences.

Now, I’m guessing that most people reading this are probably younger (or young at heart) 😉 and still in the retirement saving stage of life, so I’m not going to focus much on the withdraw rules. For now, let’s just look at the contribution rules. Or to put it another way, how do we get money into these accounts in the first place?

Now if you want to fund an IRA or a Roth IRA, you must have earned income (not passive income like dividends, interest, pension or Social Security). Second, you can contribute up to the maximum limit (which is $5,500 as of 2016) in either an IRA or a Roth IRA. And third, you can only choose one or the other for your contribution, you cannot choose both. In other words, you can put up to $5,500 into either an IRA or a Roth IRA, but not both.

How they Are Different

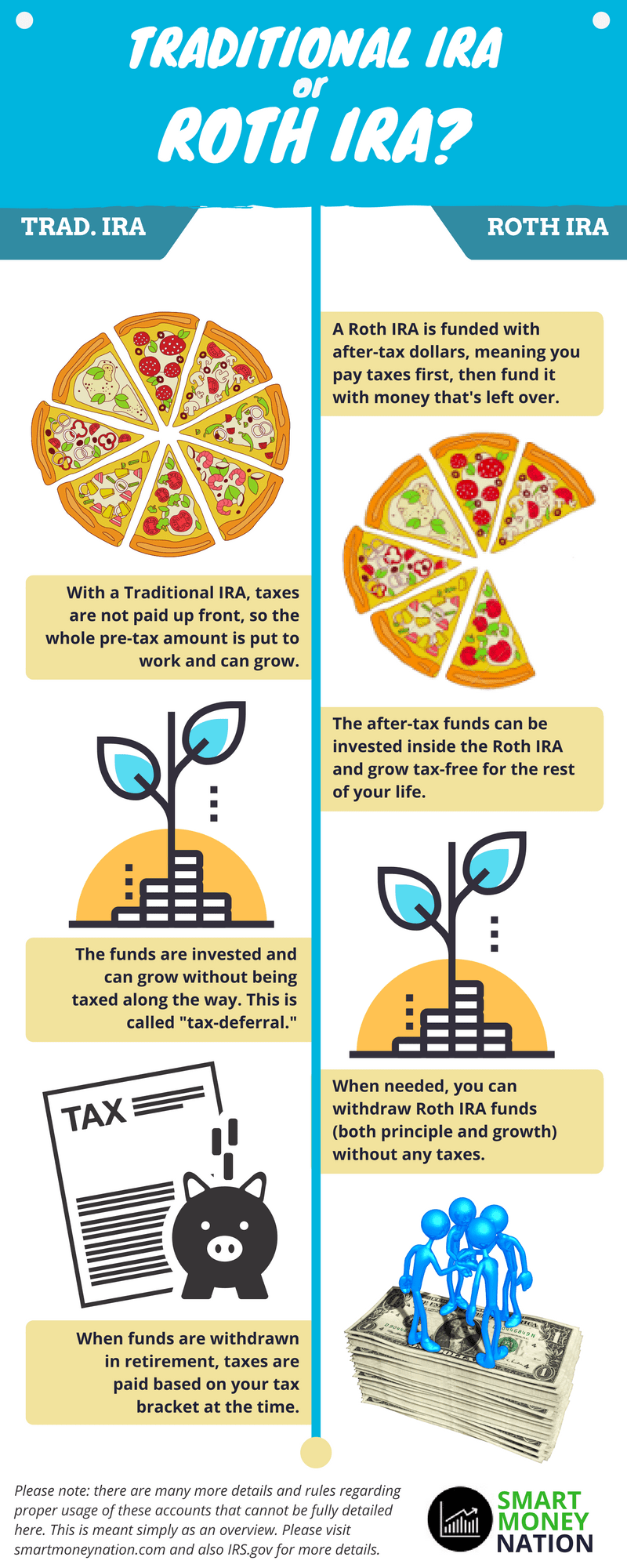

So why would you choose one over the other? This has to do with taxes, because that is the fundamental difference between the two accounts. The Traditional IRA is designed to give you a tax deduction up front, when the money goes in. Then later on in retirement, when you start to withdraw the funds, the withdraws get taxed just like any other form of income. So the tax advantage is received at the time of your contribution into the plan.

The Roth IRA, on the other hand, is the exact opposite. When you contribute the funds, you receive no tax deduction. In fact, the money you contribute has already been taxed as income. To put it another way, the money you contribute is part of the funds left over after being taxed. For that reason, it is called “after-tax” money. Once you put it in the Roth IRA, it can be invested and grow, and then when you withdraw funds in retirement, there are no taxes. So, in this case, the tax advantage is received at the time of your withdraw from the plan.

Why You Would Choose One Over the Other

Now remember, you can only choose one or the other for your contribution. So why would you choose one over the other? Typically it comes down to two things:

- What is your tax bracket today?

- What is your tax bracket going to be in retirement?

The first question is easy to answer. Below is a chart of the tax brackets for 2017 for your reference. The second question, however, isn’t nearly so easy to answer, because it involves both predicting the future of tax rates and your own personal situation. Obviously, if you and I could predict the future, we would not be focused on tax strategies. (If I could predict the future, I would soon be a billionaire and could hire an army of tax nerds to solve these sorts of problems for me. Sadly, I’m not blessed with those sorts of skills.)

| Tax Rate | Single | Married Filing Joint |

| 10% | $0—$9,325 | $0—$18,650 |

| 15% | $9,325—$37,950 | $18,651—$75,900 |

| 25% | $37,951—$91,900 | $75,901—$153,100 |

| 28% | $91,901—$191,650 | $153,101—$233,350 |

| 33% | $191,651—$ 416,700 | $233,351—$416,700 |

| 35% | $416,701—$418,400 | $416,701—$470,700 |

| 39.6% | $418,401 or more | $470,701 or more |

Still, making this decision requires some sort of opinion about the future, and I suppose the safest assumption is that the current progressive tax system stays relatively the same in the future. Many argue that taxes must go up due to our current deficits and national debt, but the counterpoint to that is that countries have run higher deficits and debts than ours, and that a decision on tax rates is not necessarily just driven by economics, it is also a function of politics. In the long-term, it probably is driven largely by economics, but in the short term, politics make the laws. (Obviously, in the very short-term the new administration is probably going to lower tax rates over the next few years, but the comments above are focused more over longer-term periods than just the current presidential cycle.)

But even if we assume a tax bracket similar to our current system, taxes for individual retirees in retirement typically go down, because of the incentives for those over age 65 already built into the tax system, both on a federal and state level. In my experience running tax projections for clients, the total tax bill relative to income usually goes down slightly in retirement.

So, Which Should You Choose?

There’s one more wrinkle that complicates this decision, and it is called the MAGI income limits. (Without diving into all the tax details, MAGI simply refers to your Modified Adjusted Gross Income.) For our purposes, just think of this as your income. Most people can just take their salary and add any self-employment income (net of any business expenses), and that figure will get you pretty close. (If you have a complex financial situation, you should ask an accountant to help you with this.) Once you know your MAGI, take a look at this following limits:

| Single | Married Filing Joint | |

| Traditional IRA | $61,000 | $98,000 |

| Roth IRA | $117,000 | $184,000 |

| Note: For the Traditional IRA, this assumes that you have access to a workplace retirement plan, such as a 401k or 403b. For those who do not, there are no income limits to worry about. Please note that these are the beginning amounts of the range in which your contribution begins to be “phased out,” but I use these amounts for simplicity sake. Also, if you are married and your spouse is covered under a retirement plan such as a 401k, you probably should discuss this with an accountant or financial planner because special limits apply. | ||

As you can see, the Traditional IRA has a much lower phase-out than the Roth IRA, which is exactly the opposite of what we would like, since we have already determined that the lower the tax bracket we are in, the more likely a Roth IRA is the best option from a tax perspective. For this reason, people who are in higher tax brackets often choose to utilize their workplace retirement plans (think 401k, 403b, 457 plans, etc.) first, even though most of the time their investment options are more limited in those types of plans. They may also have a matching program or other incentives to funding a 401k, which again may possibly trump the simple tax decision described earlier.

(To complicate things even further, most 401ks now offer “Roth” 401k accounts, which means you can fund an after-tax account like a Roth IRA, without having to worry about the MAGI income limits at all.)

Conclusion

So what’s the bottom line? For those in a relatively low tax bracket today, who may potentially be in the same or higher tax bracket in retirement, and who do not have access to a Roth 401k with matching incentives, they should focus on saving into a Roth IRA now, in lieu of the Traditional IRA. Conversely, a saver in a higher tax bracket today with the same general situation should consider a Traditional IRA.

What are you thoughts on this? Do you have a different strategy to share? If so, I’d would love to hear it. Please leave a comment below.