Coming out of the Great Recession, the US government was doing just about anything it could to stimulate the economy. First, we tried the stimulus package, which was an attempt to stimulate the economy directly through spending on infrastructure projects, support for low income workers and the unemployed, direct cash payments to recipients of Social Security, healthcare support, and tax breaks. It was based on the Keynesian economic theory that government spending should pickup the economic slack when private businesses and personal incomes suffer.

Did it work?

Well, whether the stimulus package was successful is up for debate (some say yes, and yes, others not a chance), but one of the ideas behind it was to keep the economy from descending into a deflationary spiral, something that history has taught us is very bad for all of us (poster child = Japan).

Since then, there has been a lot of hand-wringing by investors about the growth in the national debt due to programs like this. The thinking goes: if debt keeps rising, how will the government pay it off? Worse, if the debt level gets “out of control,” won’t the market require higher interest rates on government bonds? Those higher rates, then, will further exasperate the problem, because now the government has to pay even more in interest on the debt. It becomes a vicious cycle of more debt leading to higher interest rates, which leads to more debt, which leads to higher rates, and so on ad infinitum.

Eventually, governments resort to the only other recourse they have to pay their debts — printing money. And when they print money, it in theory devalues the currency, which then makes everything we import from another country more expensive.

Hello inflation, come right in and make yourself at home.

So What Exactly is This Inflation Thing?

Inflation is simple. It’s when the prices for things you need to buy are going up. For example, the price of a gallon of milk in the U.S. cost about $2.50 twenty years ago. Now, that same gallon of milk will cost you around $3.25, on average. That means we have had milk inflation of around 30% total over that time period, or about 1.3%/year.

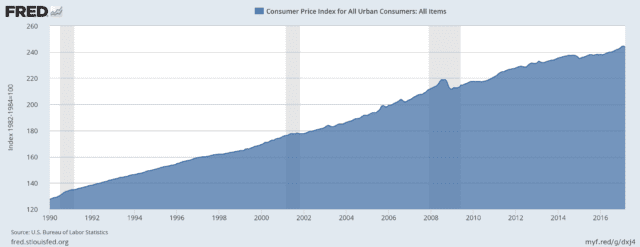

Here’s a chart of general inflation in the U.S. since 1990:

While we haven’t had a lot of inflation over this time period, we have had a fairly steady, moderate amount. Calculating the average annual inflation rate from 1990 to 2016 is fairly simple and comes out to about 2.5%. Going all the way back to 1926, the average is about 3%.

These average rates sit nicely in the “moderate” range that the Federal Reserve thinks is a reasonable and desirable inflation rate.

Why Deflation is Bad

Before we discuss why some inflation is good for the economy, we should look at one of the alternatives: deflation. Deflation is simply the opposite of inflation; it’s when prices are going down instead of up. On its face, that sounds like a really good thing. Imagine how that would help your budget if things got cheaper and cheaper each year?

The country of Japan is the poster child for runaway deflation. After a massive real estate and stock market crash in the 1980s, the former asian economic powerhouse has found it incredibly difficult to get its economy going again.

One of the main reasons for this is something John Maynard Keynes called the “paradox of thrift,” which says that if consumers believe that the price of something will get cheaper in the future, they will tend to delay their purchases. This psychology flows through to businesses, who believe they will sell less next month than they did this month. So, they invest less into their businesses, lay off employees, and reduce costs as much as possible.

This creates a vicious cycle of its own, with consumers and businesses both running towards the recessionary cliff together.

Why Some Inflation is Good for an Economy

That’s why it’s actually healthy for an economy to have a modest amount of inflation. Without it, the paradox of thrift kicks in and consumers tend to put off their purchases until tomorrow, because things get cheaper as they wait.

That kind of behavior is obviously good on an individual level, because saving for the future is a necessary and important part of financial planning. But if everyone does that, businesses sell less goods and services, and therefore get into “hunker down” mode themselves. They stop investing in new factories and equipment, which hurts other businesses that build factories or make equipment, and then those businesses start laying people off as well.

Welcome back, vicious cycle.

Conclusion

I’ve not attempted to talk about hyperinflation here, which is obviously also bad (Venezuela being the most recent poster child). That being said, a moderate amount of inflation is, on the whole, a good thing.

However, what this means for those planning for the future (uhm, everyone?) is that if you aren’t taking into account at least a moderate amount of inflation in your plans, you are making a huge mistake. That’s why very few people are rich enough to afford leaving all their money in cash over their lifetimes. Your investment portfolio must make at least a modest return above the inflation rate over the long term.

In addition, retirees in their sixties can easily expect to live twenty years or more in retirement. If their budget does not include the effect of inflation, they may find themselves with the same income in their eighties but only able to buy half as much as they could before.

The best approach is to factor inflation into your planning as best you can, with an understanding that a little bit of inflation helps the economy tick, which is good for all of us.